07 Dec 2018

US-China trade: finding the compromise

A US-China trade compromise appears to be bumping towards some sort of conclusion. At this stage it appears likely to involve concessions from China to buy more US products, improve market access for US companies and address the running sore of intellectual property theft.

That’s the better news. But a breakthrough deal that mitigates the threat of a US-China trade war and ugly consequences for a global trading system cannot disguise underlying problems in the global economy. Or continuing trade tensions, for that matter.

"From an Australian perspective, a slowing Chinese economy is a particular concern.”

As US and China negotiators resume talks this week on vexed intellectual property and other contentious issues, with a view to reaching some sort of a framework trade agreement by a March 1 deadline, warning signals accumulate about a global economy under stress.

From an Australian perspective, a slowing Chinese economy is a particular concern. One third of Australia’s exports, mainly iron ore and coal, are shipped to China.

Trade in services, principally tourism and education have also become staples. In 2017-18 education services accounted for about 8 per cent of Australia’s exports, some $AU32.4 billion in revenues for international students from China.

Chinese tourism is becoming an increasingly important component of the tourism business overall. In 2017-18 Chinese tourists spent $AU11.3 billion in Australia, about one-quarter of all tourism receipts.

Australia’s economic dependence on China and could hardly be demonstrated more starkly than by these numbers.

Trade talks

That is why economic tremors such as the latest Caixin/Markit Manufacturing Purchasing Manager’s Index (PMI) spark concern. This was the second consecutive month of contraction in China and the lowest reading since 2016. Anecdotal reports speak of widespread lay-offs of workers in businesses hit by falling domestic and international demand.

Against this background US-China trade talks assume greater significance than might have seemed the case when President Trump first imposed tariffs ranging between 10-25 percent on $US250 billion worth of imports in July last year. China retaliated by levying tariffs of between 5-10 percent on $US60 billion of imports from the United States.

China’s retaliation fell most heavily on US agricultural exports, notably corn and soybeans, so much so the US Treasury has been obliged to compensate farmers hit hard by unsold stockpiles in the mid-west.

Six months later China’s economy is continuing to soften, in the process exerting pressures on Chinese negotiators to reach a deal to guard against a further slowdown. The US would also understand it is in no one’s interests for China’s deceleration to impact the wider global economy.

However, negotiators would not be doing their job if they did not seek to take advantage of circumstances that have accrued to the American side as a consequence of China’s own concerns about its economy slowing to rates not seen in several decades.

In other words, the negotiating environment has shifted since trade talks began in December last year after US President Donald Trump and his Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping agreed on the margins of the G20 Buenos Aires summit to a 90-day window by March 1 to resolve trade differences.

Broadly, negotiators have been focusing on the following issues:

- restrictions on foreign ownership of automobile manufacturing where China requires 50 per cent local ownership;

- issues of forced technology transfer as a condition for US investments in local enterprises;

- non-tariff barriers that China applies arbitrarily to protect its domestic industries;

- cyber intrusions and cyber theft;

- services;

- agriculture; and

- intellectual property protection.

The last one may well prove to be most difficult issue. China has undertaken repeatedly to crack down on IP violations but its actions fall well short of its commitments.

Periodic moments

In the International Monetary Fund’s World Economic Update, January 2019 chief economist Gita Gopinath warns of risks of a further weakening of the global economy after the IMF had earlier revised down its projections for global growth for 2019, from 3.7 per cent to 3.5 per cent.

“The further downward revision since October in part reflects carry over from softer momentum in the second half of 2018… Risks to global growth tilt to the downside,’’ Gopinath warns.

She cites factors beyond the US-China dispute likely to impact global growth. These include high levels of public and private debt; a ‘no-deal’ withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union; weakness in German manufacturing due to the introduction of new automobile emissions standards; concerns about sovereign and financial risk in Italy; a deeper-than-anticipated contraction in Turkey; and a more pronounced than anticipated slowdown in China.

In view of the latest PMI readings a slowing Chinese economy, irrespective of a likely compromise in the US-China trade dispute, is shaping as the most concerning issue for the global economy, one with worrying implications for Australia.

“China’s economy will slow due to the combined influence of needed financial regulatory and trade tensions with the United States,’’ Gopinath of the IMF says in her briefing note.

She blames China weakness on regulatory tightening to rein in shadow banking activity and off-budget government investment against the background of trade tensions with the US.

Gopinath warns China’s economic instability “can trigger abrupt, wide-reaching sell-offs in financial and commodity markets that place its trading partners, commodity exporters, and other emerging markets under pressure”.

In other words, the world is entering one of its periodic moments when risk is elevated more or less across the board.

China’s weaker growth outlook is bringing down growth in emerging and developing Asia to 6.3 per cent in 2019 from a previously forecast 6.5 per cent.

No winners

Gopinath notes lingering uncertainty in the US-China trade wars is having a ripple effect on global confidence.

“Global trade, investment, and output remain under threat from policy uncertainty, as well as from other ongoing trade tensions,’’ she writes. “Failure to resolve differences and a resulting increase in tariff barriers would lead to higher costs of imported intermediate and capital goods and higher final goods prices for consumers.’’

From an Australian perspective, KPMG Australia’s Economics and Tax Centre has produced a useful paper (albeit a bit out of date given the likelihood of a deal). Trade Wars: There are no winners addresses consequences of relatively open trade to restricted trade between the world’s two largest economies.

KPMG sketches out three scenarios:

- limited escalation, no contagion, in which a so-called ‘trade war’ does not extend beyond existing tariff increases;

- full escalation, no contagion in which retaliatory tariffs of 25 percent are imposed by both countries; and

- full escalation, full contagion in which an all-out tariff war developed involving other countries raising tariffs by 15 per cent.

Under a limited trade war with no contagion to other countries, KPMG estimates Australia’s GDP could be around 0.3 percent lower after a couple of years, equating to a loss of $AU36 billion in present value terms over a decade.

However, if trade disputes escalated consequences would be dire.

“An all-out trade war would plunge the global economy into a recession. If financial markets got the jitters and over-reacted to such a trade war all bets would be off and a global recession would occur,” the report states.

Given the stakes involved for both the US and China, not to mention the broader global economy, that scenario is least likely. What seems more likely is a deal that enables presidents Trump and Xi to meet either later this month or early next month to announce a face-saving compromise.

Working in favor of a deal, apart from its logic in a fragile economic environment, is that both Trump and Xi need to demonstrate from the standpoint of their own domestic constituencies an ability to reach an agreement that underpins a continued global expansion.

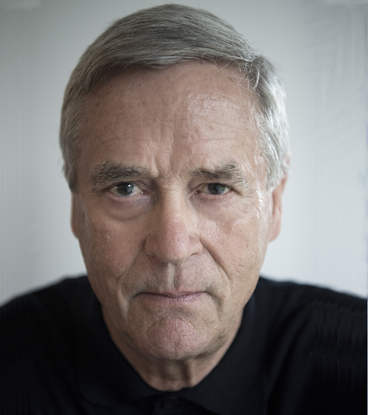

Tony Walker is a bluenotes contributor, former Financial Times correspondent in China and former Australian Financial Review political editor

The views and opinions expressed in this communication are those of the author and may not necessarily state or reflect those of ANZ.

editor's picks

09 Jul 2018